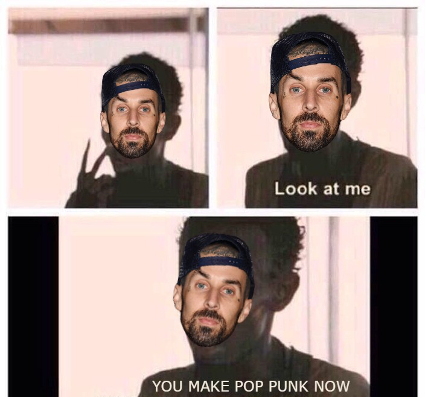

But what about subcultures then? I mean, if we are really to believe that the whole postwar youth culture thing somehow came to a crashing halt following the death of the hipster in the mid-twenty-teens, then how come older subcultures still seem to be thriving and even leaking back into the mainstream? Kids on the internet are making memes about how Blink-182’s Travis Barker almost single-handedly shaped a recent pop punk revival within the hip-hop world, hardcore punk bands like Turnstile are mixing pop into their formula and getting nominated for Grammy Awards, and there even seem to be rumours about a fourth wave of ska.[1] But the point here isn’t that subcultures have all somehow died all of a sudden, nor that the idea of authenticity has been entirely abandoned by those subcultures, but that, especially for younger generations, these questions no longer carry the same weight they once might have, and can thus be seen as exemplifying a somewhat “old school” and perhaps even outdated mode of thinking about subcultural identity. More importantly for the purposes of this chapter, however, is the way in which the central logics of memetic aesthetics have managed to permeate even some of the most orthodox subcultural spaces while remaining virtually undetected. I explore such an instance here, citing the development of the twin categories of chain punk and egg punk as a noteworthy example of the memetic aestheticization of subculture.

Every now and then, a meme will drop which so aptly captures an emergent structure of feeling or cultural formation that it gives us a new language with which to describe it. This is exactly what happened to the North American DIY punk community on July 10th, 2017, when Instagram user @xanaxylrose2000 posted the infamous chain punk/egg punk chart. Drawn on a sheet of white paper with a blue sharpie, the chart places several popular bands from across the punk circuit on a spectrum between chain punk and egg punk, with New York’s Dawn of Humans (“the egg punk band for chain punks”) and Western Massachusetts’ Hoax (“the chain punk band for egg punks”) placed squarely in the middle. Within hours, the social media accounts, message boards, and blogs of participants of the international punk community were ablaze with reposts, comments, critiques, and questions; YouTube channels were sorted into chain and egg designations, with No Deal and RICKVARUKERSPUNX associated with the former, and Jimmy with the latter; and a host of new variants on the meme were circulated, like one which added top and bottom (not pictured) and good and evil as additional axis, or another which placed various preparations of eggs along the chart. Even John Mayer famously weighed in at some point, posting on his Instagram story at the height of the craze that he was “100% egg punk.”

What @xanaxylrose2000’s chart captured so perfectly was an unspoken rift which was beginning to grow within the punk circuit by the early twenty-teens. Over the course of the 2000s, much of the North American punk scene had fallen under the reign of the hipster—such that by the end of the decade, the crowd at a local DIY gig quite often looked like the inside of an American Apparel store. As the colossal meta-subculture to end all subcultures began to crumble however, the landscape began to change: Vice-sponsored punk parties strewn with endless free cans of Pabst were no longer a thing, hipster-adjacent subgenres like garage punk, noise pop, and 1980s throwback American style hardcore punk began to go out of fashion, and in a dialectical turn against the clean-cut American Apparel minimalism that had come to saturate so much of the fashion within the scene, punk began to look, well, punk again. As hype beast neon fitted caps and Supreme five-panels were traded in for berets and shoe-string hairbands, and selvedge denim for brightly painted vintage jeans or patched up, unwashed crust pants, punk maximalism was back in.

The turn toward maximalist aesthetics after the fall of the hipster itself feels like a symptom of the memetic aesthetic shift we discuss here. As a capacious meta-subcultural amalgamation of scenes, hipsterism bore no allegiance to any specific style of dress so long as it was vaguely alt/authentic and didn’t look too try-hard. In this context, one could be just as “punk” decked out in a wool cardigan or a studded leather vest. The balkanization of this cultural common ground, however, gave a newfound salience to the distinctions between different subcultural aesthetics competing with one another in the subcultural sphere. In this new era of hashtagged minutiae, ideological commitments to the punk ethos began to feel like they mattered less than simply dressing the part. In the words of the band Who Killed Spikey Jacket? who we will return to momentarily: “Punks Dress Punk.”[2]

Yet, the death of the hipster also opened something of a power vacuum within punk style, and the maximalist style of post-hipster punk ultimately came to take one of two forms. The thing that later came to be known as chain punk was a turn toward a crustier, more orthodox punk style. Musically, hardcore punk was still very much in, but the more straightforward American hardcore sound that had prevailed throughout the 2000s had become a vessel for a host of international punk influences, such as the crusty d-beat style hardcore punk of England’s Discharge and its many Swedish and Japanese emulators (Anti-Cimex, Shitlickers, Totalitär and Disclose, to name just a few), the raw animalistic fury of Finnish bands like Kaaos and Terveet Kädet, and fuzzed out guitar tones of bands from the Japanese island of Kyushu such as Confuse, Gai, and The Swankys. Fashion-wise, this entailed a turn towards punk orthodoxy that might have felt a bit “on the nose” in the height of the hipster years. Patches, black denim, leather jackets, chains, bullet belts, studs, charged hair, jewelry, BDSM accessories, and full sleeves of tattoos were back with a vengeance. Arguably one of the best examples of chain punk’s stylistic shift is the Boston-based pogo punk band Who Killed Spikey Jacket? whose fervent ideological emphasis on punk style resulted in memorable song titles such as “Leather Loves Studs” and “Spike Your Hair with Beer.”[3] On the band’s eponymous song, singer Chris Pittman rants:

There was a day when the sea of spikey jackets stretched across the horizon. Now the spikey jacket is gone, replaced by revolting, repugnant garbage. There are people who think it is punk to dress up like somebody’s dad or like a sexy lumberjack with a rat tail. These people are wrong. They must be stopped, and their ideas destroyed. Punk music is for punks. It is not for glam rockers, or for stylish fake vampires with pointy shoes. If you are ashamed to wear studs, you should be ashamed of yourself. The spikey jacket is the armor of the punk warrior of today. You must fight for it or die trying. Long live punk! Long live oi! Long live spikey jacket! What are you waiting for? Stud your jacket, stud your vest, stud your face! Do it today you bastard! If you don’t wear studs, fuck you![4]

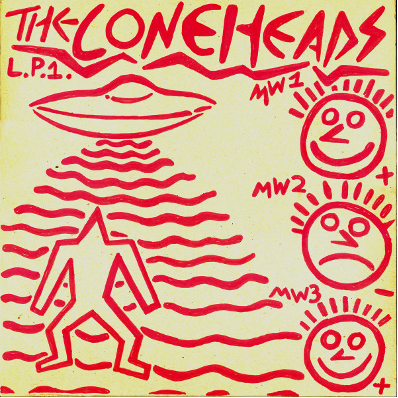

As chain punk bands began flourishing in a growing network of largely coastal urban centres such as New York, Boston, Los Angeles, Portland, Montreal, Toronto, Austin and Vancouver, a different little scene was starting to brew in the American Midwest and South. Oozing out of larger cities like Chicago, St. Louis, and Kansas City, but also smaller towns such as Bloomington, Indiana; Hammond, Indiana; Springfield, Illinois; Hattiesburg, Mississippi; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; and Denton, Texas, egg punk embraced the zany, weird, and playful elements of punk, with a synaesthetic world which looked and felt like watching Nickelodeon cartoons on an acid trip. In contrast to the apocalyptic imagery, spikiness and punk-for-punk orthodoxy of chain punk aesthetics, egg punk drew inspiration from new wave acts like Devo and the B-52s, psychedelic rock, and some of the notable freak aberrations from the 1980s American hardcore scene such as Flipper, the Dead Kennedys, the Crucifucks, Minutemen, No Trend, United Mutation, and Saccharine Trust, pairing it with a childish, naïve and Crayola-hued visual aesthetic in order to create an immersive atmosphere of total weirdo creativity. The name itself captures the evokes the genre’s wiggly, gooey, and flimsy sonic and visual textures, while also serving as a reference to a trend in which eggs became a recurring theme in its oddball aesthetics.[5]

What was particularly noteworthy about chain punk and egg punk wasn’t their colourful names with references to non-musical objects such as food items—a tendency which had been foreshadowed a few years prior with the short-lived “pizza thrash” designation—nor their dialectical turn toward maximalist aesthetics within the punk community.[6] Rather, it was the speed with which these designations conquered the hearts and minds of participants within the broader scene. As mentioned in Chapter 3, punk culture since the 1980s has been instilled with a puritanism which is distrustful of mainstream culture and mass media to a degree that borders on asceticism. A key element of this puritanism is the slow grassroots pace of punk preservationism, which ascribes a sense of cultural authenticity to the old way of doing things. Reviving underground subgenres from the 70s, 80s, and 90s, releasing music on dead formats such as vinyl and cassette, and inheriting painstaking and dated methods of production, such as recording on TASCAM 4-tracks, hand-dubbing demo tapes onto recycled cassettes, or physically assembling collage art serve as just some of the techniques which the DIY punk scene has adopted to keep the high tides of late capitalist commodification at bay.

Now historically, this steady grassroots pace also informed practices of gatekeeping meant to ensure the “purity” of the subculture, be it the legitimacy of Lady Gaga’s use of punk aesthetics in the music video for “Telephone”—in which she famously wore a leather jacket emblazoned with patches of legendary 1980s hardcore bands such as Doom and G.I.S.M., or how new cultural designations such as sub-genres and styles would be received. Hours would be devoted to longwinded Talmudic discussions on message board forums and conversations at local gigs concerning whether or not designations such as “mysterious guy hardcore” or the aforementioned “pizza thrash” were really a thing, and which bands were to fall within said designations if this were to be the case.[7] But now things had changed—a pair of sub-genre categories that seemed to have just appeared out of thin air somehow managed to bypass the rigorous verification process and took the entire scene by storm within a matter of hours. The almost universal acceptance and adoption of chain punk and egg punk then, felt something akin to the newest Gen Z TikTok dance craze making its way into the local mosh pit before receiving the proper seal of approval from the scene elders—it was all happening too fast. Chain punk and egg punk may thus be cited as examples of the memetic aestheticization of subculture—all somebody had to do was to name them and circulate a meme on social media for these categories to come to life and animate the conversations of punks from across the community.

Yet, the chain punk/egg punk meme did more than just circulate rapidly through the DIY punk network—it also changed the nature of the scene. While chain punk relied on a relatively cohesive aesthetic which had been standardized by crust punk and d-beat bands over several decades, egg punk still existed in a fluid, ambiguous and emergent state prior to the circulation of the meme. Previously described along the lines of “weirdo punk,” the scene which became designated as egg punk was a site of creative experimentation in punk, an aesthetic free-for-all for anyone who chose to defy the more orthodox sensibilities of the stud and leather inclined. As soon as it was placed in a box and codified as a genre however, egg punk died. This may be in part because of a sense of collective embarrassment at having participated in a scene called egg punk, and also in part because the scene naturally drifted, but it was also because the vast sonic perimeters which the scene allowed had been whittled down to a caricature represented by only a small handful of bands, resulting in a bland second wave of artists who interpreted the genre solely based on their limited understanding of it from YouTube and Spotify playlists.

In addition to their bold demonstration of the power of meme magic, the ability of these categories to instantaneously bypass the arduous and time-consuming process of subcultural authentication also exemplifies the lack of emphasis memetic categories place on subcultural authenticity. To the old school subculturalist of yore, the influx of memetic aesthetic categories emerging from platforms such as TikTok and Instagram spells unmitigated catastrophe. The growing fear that all it now took to be part of a subculture was to go to the mall and buy an outfit had already been brewing throughout the respective popular explosions of grunge, death metal, SoCal pop punk, mall goth, and emo in the 1990s and 2000s. But in the age of memetic aesthetics, this concern no longer even seemed to matter anymore. The cardinal sin of poseurdom had been pardoned, and one didn’t have to subscribe to a particular aesthetic anymore—they could just as well order a whole gamut of different aesthetics from AliExpress and wear a different style for each day of the week. What is particularly disturbing about this from what we might call a more “old school” (read: millennial and Gen X) subculturalist point of view is that it betrays a sense of what Mark Fisher terms “capitalist realism” on the part of today’s youth cultures.[8] There’s a sense that subculture’s subversive power and semiotic resistance against mainstream culture which had long been championed by Dick Hebdige and the Birmingham boys has been so diluted by the tsunami of late capitalist commodification that even mentioning the authenticity question seems to evoke a sense of mournful embarrassment that we were ever so gullible to think that our studded jackets and anarchy symbols could keep our precious scene from being coopted.

If memetic aesthetics pose a threat to the meticulous order of DIY punk’s purity from mainstream digital culture, the memetic aestheticization of punk coming from within its own ranks and immediately being accepted by the larger community spells big changes ahead for the notion of subculture in general. At a time when punks have become the agents of their own memeification, we might find ourselves wondering what an aesthetics of resistance of the post-internet age might look like, or if such a concept can even exist in this post-authentic world. We might also ask if gatekeeping will still remain a thing in a memeified subcultural milieu, and what purpose it will continue to serve if so. And while it feels too early to be making grand proclamations about the future of subculture in the age of digital circulation, we may put a little spin on Japanese hardcore icons G.I.S.M.’s famous slogan and claim with certainty that “punks is memers.”

[1] See: Jessica Lipsky, “Ska Lives: How the Genre’s Fourth Wave Has Managed to Pick It Up Where the ’90s Left Off,” Billboard, Apr. 25, 2019, https://www.billboard.com/music/rock/ska-lives-fourth-wave-interrupters-pick-it-up-8508727/.

[2] “Punks Dress Punk,” track # 8 on Who Killed Spikey Jacket? Who Killed Spikey Jacket? Total Fucker Records, 2012.

[3] “Leather Loves Studs” & “Spike Your Hair with Beer,” tracks # 7 & 9 on Who Killed Spikey Jacket? Who Killed Spikey Jacket?

[4] “Who Killed Spikey Jacket?” track #1 on Who Killed Spikey Jacket? Who Killed Spikey Jacket?

[5] We can think for example of the song “Eggs” by Northwest Indiana’s Big Zit and “Eggs Onna Plate” by New Orleans’ Mystic Inane; the band Fried Egg from Richmond, Virginia; or a concert at which Calgary’s Glitter sold deviled eggs from their merch table, resulting in an egg-splattered food fight.

[6] As Reddit user GreatThunderOwl explains, “pizza thrash” was a derogatory label “aimed at bands that were emulating an ‘80s vibe and using a lot of references to ‘80s pop culture, notably Bonded by Blood, Municipal Waste, and Gama Bomb. It kind of implied it was a ‘kiddy’ version of old thrash. Notably enough not a single one of those bands has a song about pizza, but that doesn't stop people from throwing it around.” GreatThunderOwl, “Shreddit's General Metal Discussion,” Reddit, 2016, https://www.reddit.com/r/Metal/comments/43tvws/comment/czl9dp0/.

[7] “Mysterious guy hardcore” was another sub-subgenre designation which emerged in the hardcore punk blogosphere of the late aughts. The term designates a wave of noise rock and black metal influenced hardcore bands using a highly aestheticized “mysterious” visual aesthetic characterized by blown out black and white photographs and the use of premodern mystical and occult imagery, and is generally associated with the Brooklyn-based label, Youth Attack Records.

[8] See: Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (London: Zero Books, 2009).